It is hard to see how arguments that President Trump cannot appoint Matthew Whitaker as acting attorney general must be incorrect. Otherwise the Constitution could deprive the nation of a functioning government every time a new party wins the presidency while the opposition party holds the Senate.

Some of those attacking Whitaker’s appointment of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) are left-wing partisans who hate President Trump and will say anything to embarrass him, but others are conservative lawyers who are making arguments in good faith, even if they are wrong.

It is always good to have lawyers argue both sides of an issue. With all the legal arguments being pressed about how Whitaker’s appointment is illegal, it seems only fair to offer constitutional arguments in support of his appointment.

The Appointments Clause of Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution provides that the president “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall Appoint … [Principal] Officers of the United States.”

Often that means that when a top government position – called a “principal officer” – becomes vacant, it remains unfilled until the president nominates someone and then the U.S. Senate has time to vet, hold committee hearings, have floor debate, and confirm the nominee. The Constitution should allow for some degree of “play in the joints” to handle such situations.

Congress’s answer was the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998 (FVRA), which provides several routes for someone to fulfill the duties of these important positions while the nomination and confirmation process plays out. First, 5 U.S.C. § 3345(1) allows the “first assistant” to a Senate-confirmed officer to serve as the acting officer on a temporary basis. Additionally, 5 U.S.C. § 3345(2) allows the president to name a person who has served in that department for at least 90 days at a pay level of GS-15 or higher – essentially a top-level career civil servant or non-Senate political appointee – to likewise serve as the acting officer.

Either way, that acting officer can serve for 210 days (seven months), and that time is extended if the president has nominated a permanent replacement but the Senate has not yet voted on the nominee.

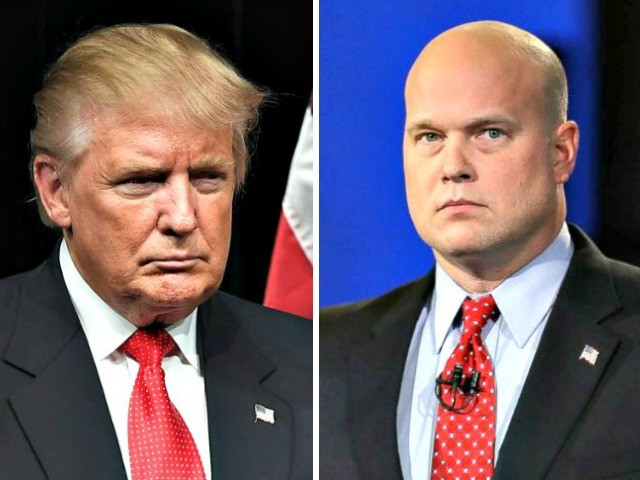

Whitaker was the highest-ranking person at DOJ who was not Senate-confirmed, as chief of staff to the attorney general. He is a “Schedule C” political appointee, meaning that he was appointed by the Senate-confirmed head of DOJ, the attorney general. He is at the top pay level in the department (above GS-15), and has held that position for more than 90 days. President Trump invoked his authority under 5 U.S.C. § 3345(2) to name Whitaker as acting attorney general until the president can nominate, and the Senate can confirm, a new attorney general.

Legal critics argue that the Constitution requires Senate confirmation as a check on the president’s power, ensuring that no president can flood the zone with legions of unqualified loyalists who would never be approved by the Senate. They argue that FVRA provides an end-run around that check, and thus that those provisions are unconstitutional.

Their argument sweeps more broadly than they might realize. If correct, their argument does more than nix the president’s ability to name someone. It also would mean that the provision allows a “first assistant,” who is most often a non-Senate officer, to take over.

For example, all 94 U.S. attorneys are Senate-confirmed political appointees. When a new president takes over and cleans house, a senior federal prosecutor in that office makes all the decisions, and signs all the legal briefs and court filings, as the acting U.S. attorney.

But under the rule proposed by Whitaker’s critics, all that is unconstitutional. All federal prosecutions must stop until the Senate gets around to confirming a new U.S. attorney in each office. That does not sound right.

These critics are perhaps forgetting Article II, Section 1, Clause 1 of the Constitution, the Executive Vesting Clause, which establishes the bedrock principle of a “unitary executive” with the words, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.”

But a president is only one human being, with a body that can work only so many hours a day, requires sleep, food, and bathroom breaks. For at least eight hours a day, he cannot run the government directly. He has only two ears and one mouth, so cannot participate in both a military briefing and an economic briefing simultaneously. He only has two hands, and so cannot sign two orders at literally the same moment. He cannot have private meetings with the president of China and the prime minister of the United Kingdom at the same time.

In short, every president needs subordinates 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for the government of the world’s lone superpower to function. The president therefore must have power to install subordinates who will carry out his wishes.

Any other conclusion would lead to the absurd choice of either crippling the entire U.S. government – including national security functions – until the Senate goes through the entire confirmation process, or persuading leaders of the opposing political party to stay in their powerful positions for weeks or months until replacements can be both nominated and confirmed.

Who else could run the government before top officials are confirmed? White House staff do not require Senate confirmation, so if the critics’ arguments were correct, these staffers cannot run the departments, either.

Even if that argument were not on the table, it would be a far greater threat to the concept of checking a president’s power through Senate approval to allow his handpicked personal advisers, who are often the most loyal to the president and often accused of more partisan behavior, to assume operational control of every aspect of the government.

Quite the contrary, so much power radiates out of the Oval Office that good government counsels that the president’s intimate advisers be a separate group of people from those managing government operations. You want the national security advisor to never have a self-serving reason to let the president know if the State Department or Defense Department is failing to implement the president’s agenda, which the national security advisor is less likely to do if he actually commands those departments. You want the national economic adviser to provide candid and critical feedback to the president regarding the Treasury Department. You want the domestic policy adviser never to have a reason to trim his sails when providing critical feedback on the Department of Health and Human Services. The list goes on.

Thus, the unavoidable result of the argument against Whitaker’s appointment is that when a new party takes the White House, the new president has no choice but retain in critical Cabinet positions top partisans from the defeated party. Although department heads serve at the pleasure of the president, henceforth no president could fire any of those top government officers until their replacements are confirmed – a process that can take weeks or months – even if those Cabinet officers blatantly and deliberately disobey the president’s orders. The new president would have executive authority in name only.

Put this in concrete terms. Imagine a Republican president like Donald Trump follows a Democrat president like Barack Obama. Imagine also that a hardline partisan Democrat like Chuck Schumer holds a majority in the Senate. President Trump is sworn in, but Schumer says he likes Obama’s current Cabinet better, and thus the Senate will go a full year without allowing a confirmation vote on a single Trump nominee for a Cabinet post.

Schumer goes on to say, “For that matter, I will not confirm a single nomination to any lower-ranking position in the entire government for the next 365 days, either.” No deputy secretaries, no under secretaries, no assistant secretaries, no ambassadors, no U.S. attorneys, etc.

President Trump orders Secretary of State John Kerry to withdraw the United States from the Iran deal, but Kerry responds, “No chance!” President Trump orders Attorney General Loretta Lynch to defend his new immigration policy to restrict entry in this country of persons from terror-prone nations like Syria or Iran, but Lynch responds, “I will actually file briefs saying that the Justice Department thinks your policy should be struck down, and by the way, the whole department will shut down if you fire me, Mr. President!” Of course, the legal defense might be a moot point, because Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson fell out of his chair laughing when he read President Trump’s new immigration policy and sent the president an email explaining that Johnson will now be making his own policies, because he just heard Schumer’s comments on television, and the secretary consequently knows that as a practical matter he cannot be fired for the next year. He will come by the White House to let his boss, the president, know which issues Johnson might be willing to negotiate over.

Then these Obama department heads agree that they will not use their statutory authority to appoint any of the lower-ranking Schedule C political appointments whom the White House wants, because federal law specifies that the heads of agencies technically make those decisions, rather than the president directly. Kerry’s chief of staff is ready to resign, but instead of the person put forward by the White House Office of Presidential Personnel, Kerry exercises his authority to grant that Schedule C appointment to someone who tweets about how much he despises both President Trump and the nation of Israel.

Lynch does the same thing at the Department of Justice. Instead of Matt Whitaker – whom the White House wants – Lynch uses her authority as attorney general to appoint a chief of staff who believes in amnesty for illegal aliens, that religious liberty protects only the right to worship in your home or church, that sex-discrimination laws covers sexual orientation and gender identity, that the Second Amendment does not apply to private citizens, and that President Trump should be impeached.

Adding insult to injury, the entire Obama Cabinet blows off President Trump’s Cabinet meeting in the White House, flying instead to Chappaquiddick to Hillary Clinton’s house. Once there, they tell her that they all voted for her, and they would like her to offer each of them suggestions that resemble presidential orders, and they promise to fly back to Washington and put those policies into effect.

Essentially, Clinton is the de facto president until Schumer decides to allow confirmation votes for Trump nominees.

This scenario sounds absurd, but would legally be entirely possible if the argument were true that only a current Senate-confirmed officer can temporarily assume the duties of another Senate-confirmed position, even temporarily, up to and including a Cabinet-level department head like the attorney general.

In other words, these critics’ argument appears to set Article II’s Appointments Clause on a head-on collision with Article II’s Executive Vesting Clause.

None of this means that the precise terms of FVRA are the best combination of policy specifics to fill that need for play in the joint when transitioning government power and personnel. Perhaps the temporary appointment should be limited to 180 days, instead of 210. Maybe it should authorize someone who has held the relevant previous job at least 120 days, instead of 90. Whitaker’s appointment satisfies any of those minor tweaks in the specific requirements.

But viewing the big picture, some mechanism to temporarily fill top government positions is necessary for a new president to take over. That being the case, there is nothing in the Constitution’s text, structure, or history indicating that transitional authority expires after a period of time. But even if it did, such a limitation would not apply here, because there are still dozens of Senate-confirmed key administration positions for which President Trump has made a nomination, but the Senate has not acted since the president took office. Take for example Charles Stimson, the nominee for general counsel of the U.S. Navy, whose nomination has been pending since 2017.

Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson once wrote that the Constitution is not a “suicide pact.” That is true politically as well. While the Constitution does divide power, and includes checks and balances, it does not do so in a way that ensures that a new president could be utterly paralyzed if the other party controls the Senate.

It is hard to see how the arguments against any president having the ability to fill vacancies of top government positions could lead to any other result.

Ken Klukowski is senior legal editor for Breitbart News. Follow him on Twitter @kenklukowski.